Crossposted at Greater Greater Washington

Crossposted at Greater Greater Washington Visitors and residents of Washington, DC know, to one degree or another, about the city's street naming conventions. Most tourists know that we have lettered and numbered streets. And to some degree, they know there is a system, but it doesn't stop them asking us directions. But most out-of-towners and even many residents don't understand the full ingenuity of the District's naming system.

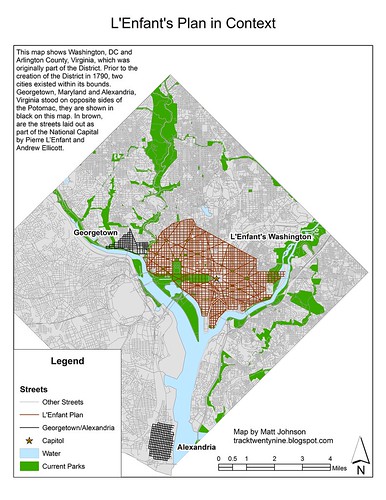

Washington is partially a planned city. The area north of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers and south of Florida Avenue (originally Boundary Street) is known as the L'Enfant City. This area of Washington was the original city of Washington, laid out by Pierre L'Enfant and Andrew Ellicott. It is comprised of a rectilinear grid with a set of transverse diagonal avenues superimposed. Avenues frequently intersect in circles or squares, and the diagonals create many triangular or bow tie-shaped parks.

Washington is the seat of government of a nation. Believing that the structure of the government should inform the structure of the city, L'Enfant centered the nascent city on the Capitol, home of the Legislative (and at the time, the Judicial) branch of the government, the one the framers held in highest esteem. From this great building radiate the axes of Washington. North and South Capitol Streets form the north-south axis; East Capitol Street and the National Mall form the east-west axis. These axes divide the quadrants.

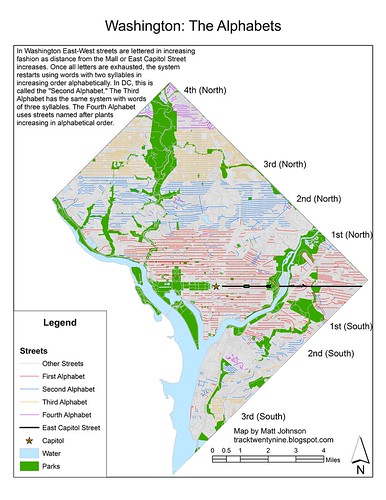

Washington is the seat of government of a nation. Believing that the structure of the government should inform the structure of the city, L'Enfant centered the nascent city on the Capitol, home of the Legislative (and at the time, the Judicial) branch of the government, the one the framers held in highest esteem. From this great building radiate the axes of Washington. North and South Capitol Streets form the north-south axis; East Capitol Street and the National Mall form the east-west axis. These axes divide the quadrants.The axes also provide the basis for the naming and numbering systems. Lettered streets increase alphabetically as they increase in distance both north and south of the Mall and East Capitol Street. Numbered streets increase in number as they increase in distance both east and west of North and South Capitol Streets.

Many street names intersect in multiple quadrants. G Street intersects Sixth Street in all four quadrants, and each of these intersections is separated by over a mile. Western, Eastern, and Southern Avenues form in many places the land boundaries of the District.

North of Georgetown and Boundary Street (Florida Avenue), the area formerly known as Washington County, DC began to develop. For the most part, developers extended the grid as the most efficient way expand the growing city. Some areas, notably Petworth, recreated the principles of the L'Enfant plan, with avenues and circles intersecting the grid. In other places, geography made a rectilinear grid impractical.

North of Georgetown and Boundary Street (Florida Avenue), the area formerly known as Washington County, DC began to develop. For the most part, developers extended the grid as the most efficient way expand the growing city. Some areas, notably Petworth, recreated the principles of the L'Enfant plan, with avenues and circles intersecting the grid. In other places, geography made a rectilinear grid impractical.As the city expanded, so did the system of naming streets. In the L'Enfant city, the highest lettered street was W Street (running between Ninth and Fifteenth Streets NW). Unlike numbers, the alphabet is not infinitely expandable. In order to continue to have an alphabetical progression of streets, the alphabet starts over. Only "streets" are subject to the convention. Avenues, roads, drives, and other minor streets do not conform to the alphabetical progression. "Places," on the other hand, usually appear one block north of the correspondingly lettered street and often share the same first letter.

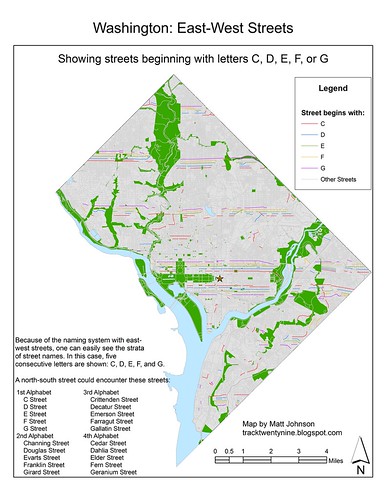

After the first alphabet runs out of letters, street names restart alphabetically with two-syllable names. "Adams Street" follows "W Street." Once the second alphabet is exhausted, the system repeats with words of three syllables. "Webster Street" is followed by the third alphabet's "Allison Street." However, the Fourth Alphabet does not use words of four syllables. Instead, the Fourth Alphabet, only present in the Northwest and largest quadrant, uses the names of plants in increasing alphabetical order. Thus "Aspen" follows "Whittier."

Typically, each of the other alphabets uses the same letters used by the First Alphabet (A-W, skipping J). However, there are some exceptions. The Second Alphabet has Yuma Street, there's a Jefferson Street in the Third Alphabet, and Xenia Street appears in Southeast. East-west streets in the District are often discontinuous due to obstructions. Sometimes the street continues with the same name on the other side, and sometimes it changes to a different name. Shepherd Street NW, for instance, is split by Piney Branch Park between Fourteenth and Sixteenth Streets, but keeps the same name on both sides. However, on the other side of Rock Creek Park, in Upper Northwest, the two-syllable "S" street name is Sedgwick. Still, a look at the first letter of streets in the District easily shows the strata of the alphabets.

Typically, each of the other alphabets uses the same letters used by the First Alphabet (A-W, skipping J). However, there are some exceptions. The Second Alphabet has Yuma Street, there's a Jefferson Street in the Third Alphabet, and Xenia Street appears in Southeast. East-west streets in the District are often discontinuous due to obstructions. Sometimes the street continues with the same name on the other side, and sometimes it changes to a different name. Shepherd Street NW, for instance, is split by Piney Branch Park between Fourteenth and Sixteenth Streets, but keeps the same name on both sides. However, on the other side of Rock Creek Park, in Upper Northwest, the two-syllable "S" street name is Sedgwick. Still, a look at the first letter of streets in the District easily shows the strata of the alphabets. The highest numbered street in the District is 63rd Street in the Capitol Heights section of Northeast. Southeast's nearby 58th Street is that quadrant's highest numbered street. In Northwest the ridges and valleys of the Potomac Valley cause numbered streets (and the grid) to give up the ghost at 52nd Street. And tiny Southwest sees its highest number with 23rd Street south of the Lincoln Memorial.

The highest numbered street in the District is 63rd Street in the Capitol Heights section of Northeast. Southeast's nearby 58th Street is that quadrant's highest numbered street. In Northwest the ridges and valleys of the Potomac Valley cause numbered streets (and the grid) to give up the ghost at 52nd Street. And tiny Southwest sees its highest number with 23rd Street south of the Lincoln Memorial. Of course, without its state-named avenues, Washington would have a far less complex street system. But the avenues don't only add complexity, they also close the streetscape, provide vistas to monumental buildings, and create squares, plazas, and parks throughout the city. These famous streets are important streets in the city, but they don't conform to the system, and as a result are more difficult to find.

Of course, without its state-named avenues, Washington would have a far less complex street system. But the avenues don't only add complexity, they also close the streetscape, provide vistas to monumental buildings, and create squares, plazas, and parks throughout the city. These famous streets are important streets in the city, but they don't conform to the system, and as a result are more difficult to find.Except for California Street and Ohio Drive, all the states have avenues named after them. The shortest of the avenues is Indiana Avenue, found near Judiciary Square and the Archives. It stretches less than half a mile, exclusively in Northwest. While no state-named avenue passes through all four quadrants, the longest, Massachusetts Avenue, passes through three. It stretches from border to border across the District, although it lacks a bridge over the Anacostia, and continues northward into Montgomery County, Maryland.

Commenting here has been disabled. Please leave comments at this same post on Greater Greater Washington.

Commenting here has been disabled. Please leave comments at this same post on Greater Greater Washington.

No comments:

Post a Comment